The Code

The RUB Code collection is a series of programs used to (1) assemble the RUB Corpus and (2) conduct a Russian-language, lexicon-based, sentiment analysis upon the RUB Corpus.

All the Code programs are written in python.

The sentiment analysis uses a modified version of the lexicon created by Loukachevitch & Levchik (2016).

To access the Code, scroll down to the “Code Download” section.

Introduction

This page describes two different groups of programs, which make up the RUB Code.

The RUB code was used to assemble the RUB Corpus and perform a lexicon-based, sentiment analysis.

The RUB Corpus was gathered using web crawling and scraping programs. Crawling is the repetitive process of accessing a webpage and inspecting its contents. Scraping is the automated gathering of data from the internet (Mitchell, 2015, pp. 31, viii).

The sentiment analysis was conducted using a standard three-step pipeline: (1) Data Acquisition; (2) Data Preprocessing; and (3) Categorisation. To conduct the analysis Russian, the author modified the RuSentiLex lexicon created by Loukachevitch & Levchik (2017).

For an introduction to Russian-language sentiment analysis, see the excellent paper by Vīksna & Jēkabsons (2018).

After this introduction and a short “Disclaimer” (below), the RUB Code can be found under “Downloads” in the “Code Download” section.

Under the table of downloadable code, there is some further explanation of how this code was designed.

The “Crawling/Scraping Programs” section explains how the crawling and scraping code was designed.

The “Sentiment Analysis Programs” section describes the series of programs used to perform a Russian-language sentiment analysis.

Disclaimer

The author of the code learnt how to use the coding languages as he wrote them. Therefore, some of the code is illogically structured and inefficient.

If you feel compelled to alert the author of any fatal errors in the RUB Code, please scroll down to the “Contact” heading for details on how to get in touch.

Code Download

To use any of the RUB Code scripts, please use the following citation:

Braga, P. (2020). RUB Corpus and Code. Project repository. Available at: https://github.com/pjbraga/rub_corpus_and_code.

The various scripts contain multiple notes and comments, which are intended to make the code easier to understand.

All the scripts uploaded here begin with a standard file header, and then a comment block with the following four headings:

- Description (a one-to-two sentence explanation of the script)

- Requirements (necessary prerequisites to run the script)

- Summary of Code (synopsis of the layout and function of the script)

- Notes (any peculiarities or potential issues with the code)

For descriptions about how the scripts work, please read the information under the “Crawling/Scraping Programs” and “Sentiment Analysis Programs” headings below.

Downloads:

| Code | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Lukashenka.py | Scraper | Scrapes transcripts of speechs, interviews, and offical press releases made by nominal Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenka |

| preprocess_2020.py | Preprocessing | Prepares Russian-Language sentences for sentiment analysis |

| Putin_PM.py | Scraper | Scrapes transcripts of speechs, interviews, and offical press releases made by Vladimir Putin when he served as Russian Prime Minister |

| Putin_President.py | Scraper | Scrapes transcripts of speechs, interviews, and offical press releases made by Vladimir Putin when he served as Russian President |

| rusentilex_2020.txt | Sentiment Lexicon | Russian-language, 4-polarity sentiment lexicon |

| saTagProcessor_2020.py | Algorithm | After preprocessing, this uses an algorithm to calculate the sentiment of lexicon tagged sentences |

| speech_to_sentence.py | Text Structuring | Finds sentences with key words, extracts them from the text, and outputs to a spreadsheet |

| tagProcessor_lib_2020.py | Function Library | a library of functions for processing sentiment tags |

Crawling/Scraping Programs

The crawling/Scraping programs are built with Python 3.7.1 (Van Rossum & Drake, 2018), BeautifulSoup 4.7.1 (Richardson, 2019) and other Python third party software (such as Pandas) to crawl webpages and scrape relevant texts (PyData Development Team, 2019; Reitz, 2019).

Regular expressions, a notation used to find and identify text (Friedl, 2006, p. 1), are also included in these programs to filter webpage contents and increase accuracy.

Under each crawling/scraping program function, there is (or should be) a short description of its use. In some cases, there are comments explaining the purpose of certain variables, regular expressions, or filters contained within the functions.

The crawling and scraping programs were designed with one guiding prinicple: to gather (as accurately as possible) only the words spoken by the policymaker/s in question.

This form of data acquisition is the first step of the sentiment analysis pipeline. The more accurate it is, the more effective the later preprocessing and categorisation steps can be.

It should be noted that crawling and scraping programs often need to be tailor-made for each website they encounter.

Sentiment Analysis Programs

After the texts are scaped, the second and third steps in the sentiment analysis pipeline can proceed.

The second step is data preprocessing. Preprocessing involves a series of data handling procedures to make a text meaningful for a given sentiment analysis program.

The third step is the categorisation process. Categorisation, also called classification, is the automated process of identifying opinions in text and deciding their sentiment. This is essentially the “analysis” part of sentiment analysis.

The sentiment analysis programs are also written in Python 3.7.1 (Van Rossum & Drake, 2018), but with an occasional need to interact with JSON APIs (servers that communiate with other systems using JavaScript Object Notation language).

The programs (downloadable above) that make up the second and third sentiment analysis pipeline steps are explained in more detail in the “Data Handling (Preprocessing) Tasks” and “Sentiment Analysis Tasks” subsections below.

Data Handling (Preprocessing) Tasks

The following subsection describes how the RUB Code prepares the scraped texts for analysis.

This RUB project preprocesses collected texts for sentence level analysis (see the speech_to_sentence.py script above). “Level” is the scope at which to conduct sentiment analysis upon a text. Sentence level preprocessing breaks a given text into sentence-sized units.

All text levels of analysis are problematic (Liu, 2015). Considerations of simplicity, necessity, and accuracy dictate the use of sentence level analysis for the RUB project.

The sentence level (while it is essentially a miniaturised version of a larger text) means the unit of analysis is not too large to be meaningless, and not too specific to complicate the classification process.

In addition, a sentence level approach suits lexicon-based sentiment analysis techniques. Lexicon-based sentiment analysis is reductive to begin with (in contrast to highly sophisticated machine learning techniques) (Dey, 2018). The aim of this project is to test and demonstrate applicability of Russian-language sentiment analysis in political science research. The development of newer, more sophisticated approaches is for computer scientists. Anything more technical is not required.

Most importantly, analysis of two test datasets built by Rubtsova (2015) at the sentence level has produced acceptable accuracy results.

Sentiment analysis accuracy is generally calculated using precision, recall, and F1 scores (Sarkar, 2019, pp. 200–204). Precision measures the proportion of correct versus false-positive sentiment predictions. Recall measures the proportion of correct versus false-negative predictions. F1 score is the main accuracy indicator, which is the harmonic mean of the two precision and recall measures.

Below are the accuracy test scores produced by the RUB Code. An acceptable F1 score is considered to be around 70 percent (Schmidt & Burghardt, 2018, p. 146). The F1 scores at the sentence level are 78.699248 percent and 83.9956279 percent for respective positive and negative sentiment test datasets.

RUB Code Accuracy Results

| Test Dataset | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F1 Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Sentiment | 92.05644 | 68.727094 | 78.699248 |

| Negative Sentiment | 85.072902 | 82.9452956 | 83.9956279 |

Once the sentence level is decided upon, the core preprocessing jobs can begin (see the preprocess_2020.py script in the listed downloads above).

Six preprocessing techniques are used in the RUB Code: structuring, cleaning, text replacement, autospellchecking, tokenisation, and lemmatisation.

Structuring refers to how the data is organised for analysis. The RUB Code tracks opinion changes over time. Thus, the data is structured for longitudinal analysis: it is arranged according to the date a speech was made or a policymaker was quoted.

Cleaning (also referred to as “scrubbing”) removes all non-sentiment-bearing elements from a sentence. Non-sentiment bearing elements include punctuation and “stop-words,” which are words that contain no sentiment, such as “when,” “this,” “that,” “after,” and so on.

The RUB Code includes text replacement. This substitutes emoticons (text representations of facial expressions, such as “:-)” and “:-(” communicating emotion), certain slang words, and other informal sentiment-bearing expressions (such as “hooray” and “boo”) with a simple equivalent word, such as “good” or “bad.”

Next, the sentences are spell-checked. The RUB Code runs a simple Russian language automatic spellchecker using the Yandex Speller API (Seleznev, 2015). Yandex is a popular Russian-language search engine, like Google.

The RUB Code then performs tokenisation. Tokenisation breaks a sentence into units that are easier for a lexicon to analyse. Individual words are called tokens, and collections of words are referred to as “n-grams” (referring to a contiguous sequence of n items in a series).

The final preprocessing task is lemmatisation. Each token is reduced to its linguistic root. For example, “walking” becomes “walk,” and “better” becomes “good,” and so on. To perform this complex function, the RUB Code employs the pymystem3 lemmatisation package (Sukhonin, 2018), which is (again) based on software developed at Yandex (Segalovich, 2003).

At this point, the texts are ready for sentiment analysis.

Sentiment Analysis Tasks

The RUB Code sentiment analysis is a function of two parts: the RuSentiLex Lexicon (a dictionary of sentiment bearing words and their corresponding sentiments; see the rusentilex_2020.txt file in the downloads table above) and an algorithm (a series of mathematical rules to decide the sentiment for each sentence processed; see the saTagProcessor_2020.py and tagProcessor_lib_2020.py scripts also in the downloads table above).

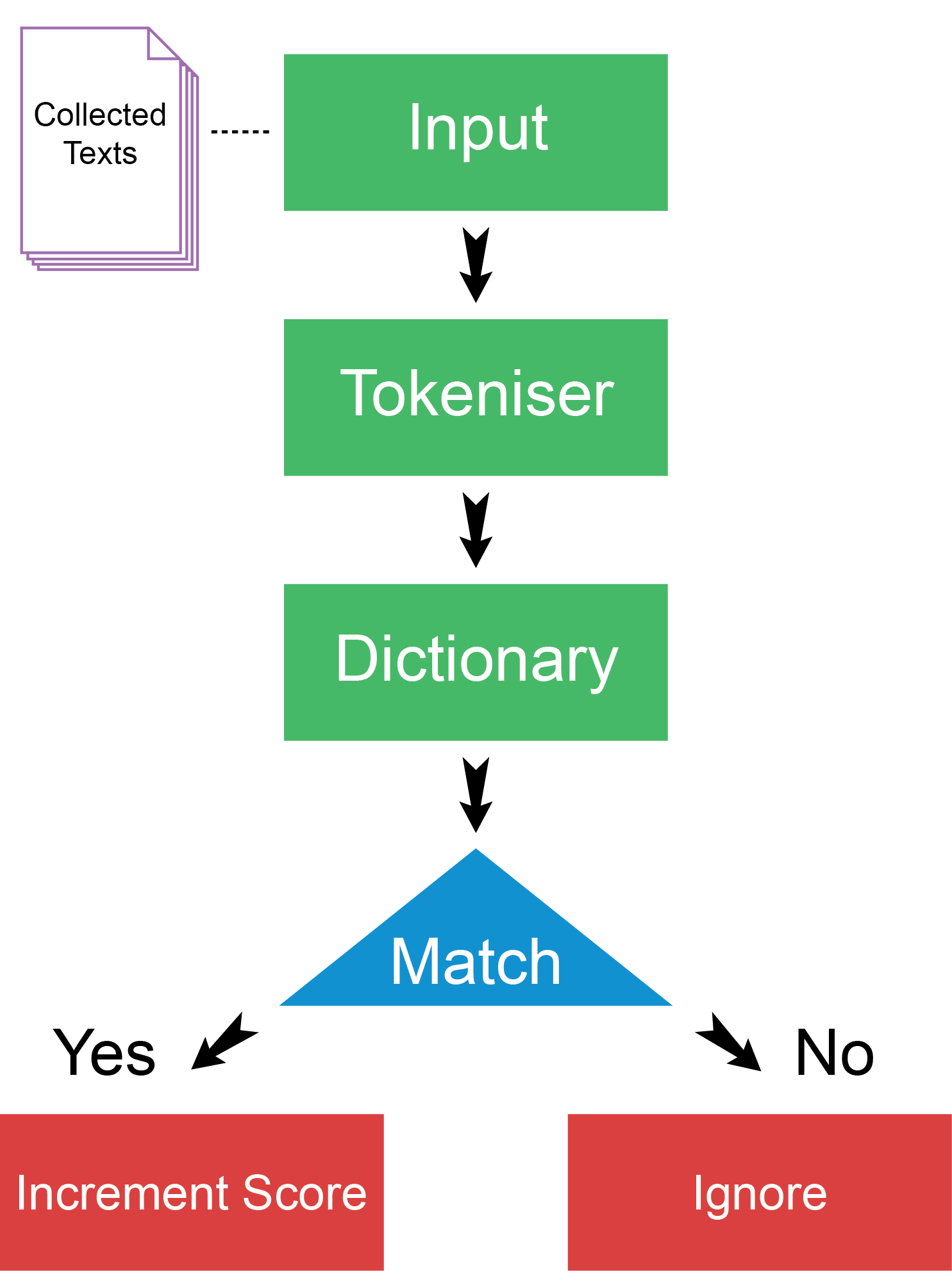

This is essentially what the process looks like:

The “Collected Texts” are assembled by the crawler/scrapers (discussed in the “Crawling/Scraping Programs” section above). The “Input” and “Tokeniser” stages equate to the preprocessing steps descibed in “Data Handling (Preprocessing) Tasks” directly above. The “Dictionary” (lexicon) and “Match” (algorithm) stages decide the sentiment of sentences. The result (in the case of RuSentiLex) “scores” one of four possible sentiments: positive, negative, neutral, or ambiguous. Sentences that cannot be matched are “ignored.”

The RuSentiLex lexicon has four different sentiment categories (also called polarities, orientations, or valencies): positive, negative, neutral, and ambiguous. Positive sentiment expresses optimism or confidence about something. Negative sentiment means something is not desirable or not optimistic. Neutral is the absence of sentiment or no sentiment. Finally, ambiguous sentiment means it is not possible to choose between a positive, negative, or neutral sentiment without further context.

The RUB Code uses a modified RuSentiLex lexicon. RuSentiLex was originally designed to test if a word or phrase with multiple connotations was used to express a fact, opinion, or personal feeling (Loukachevitch & Levchik, 2016, pp. 1172–1173). The author of the RUB Code was unable to harness this feature. Therefore, this inaccessible element is removed from the lexicon used here.

The modified version still contains sentiment orientations for all the “more than 12 thousand words and phrases,” which are the core of the RuSentiLex dictionary (Loukachevitch & Levchik, 2017).

After RuSentiLex determines the sentiment of tokens (a process referred to as sentiment tagging), a simple algorithm calculates the sentiment for the sentence.

The RUB Code Algorithm

The RUB Code algorithm functions in two stages. The first stage is a calculation to find the averages of sentiments in the sentence. The highest average sentiment (positive, negative, neutral, or ambiguous) determines the sentiment of the sentence.

This stage can be explained with the following example. A sentence is found to have 5 positive, 1 negative, 3 neutral, and 2 ambiguous tokens or n-grams. The algorithm translates this to 50 percent positive, 10 percent, negative, 30 percent neutral, and 20 percent ambiguous. Therefore, the first stage of the algorithm would rule the sentence to have positive sentiment.

The aim is that only sentences clearly displaying a particular sentiment are labelled as such.

The second stage of algorithmic rules is triggered only if the highest sentiment is unclear. If positive sentiment is equal to negative sentiment in a sentence, the sentence is labelled as “ambiguous” in sentiment. And if all sentiments are equal in the sentence, this also understood as “ambiguous.” If positive sentiment is equal to ambiguous or neutral sentiment, the sentence is labelled as “positive.” Vice versa with negative sentiment. Finally, if the sentence has no discernible sentiment, it is labelled “not classifiable” and ignored.

The RUB Code sentiment analysis is crude. But the algorithm has proven effective at identifying positive or negative sentiment sentences in Rubtsova’s (2015) large test datasets.

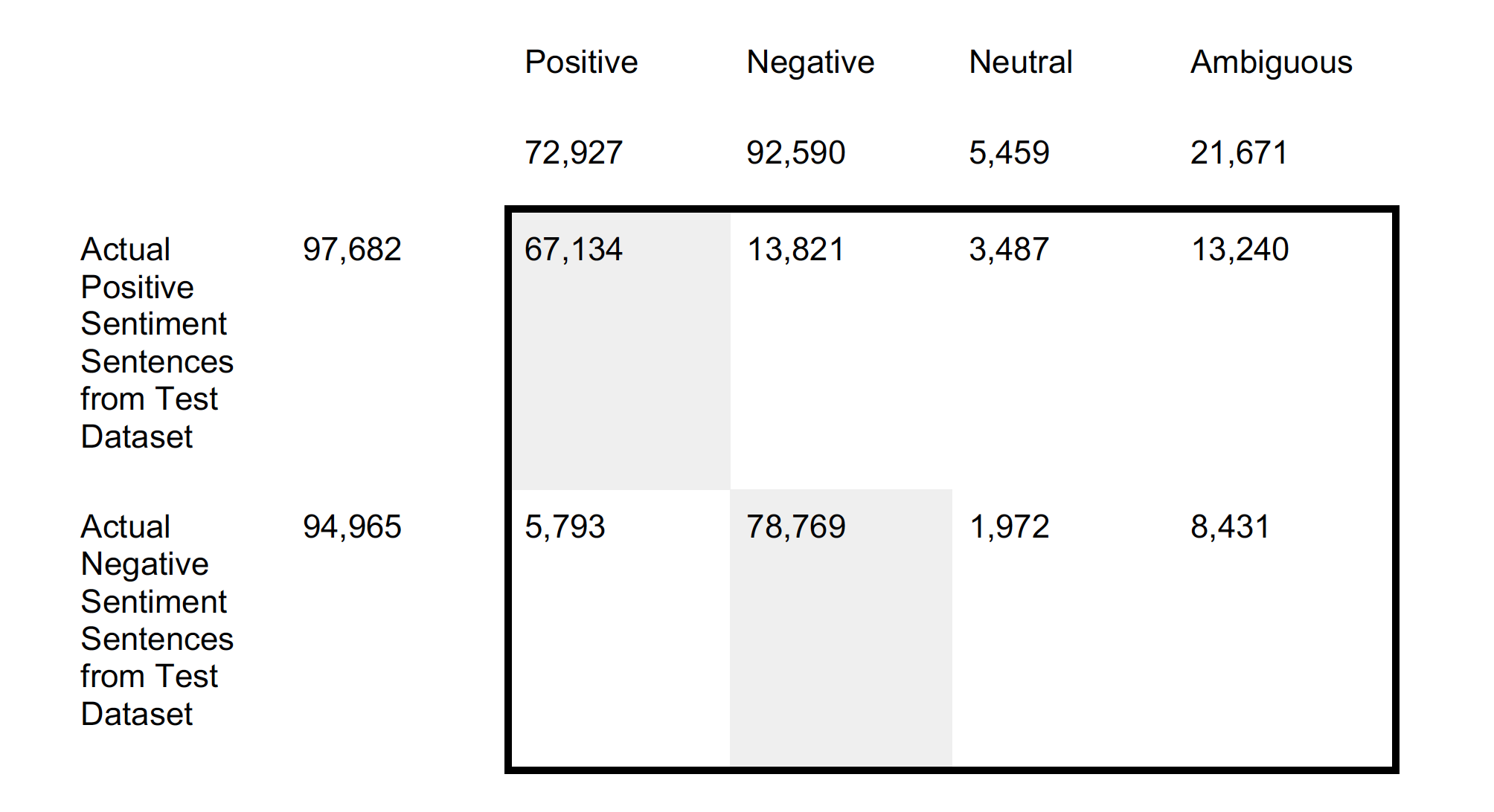

The following image is a confusion matrix, which provides more detail on the accuracy of the RUB Code’s sentiment anlaysis:

The far left-side of the matrix shows the number of sentences in the positive and negative test datasets. “Actual Positive Sentiment Sentences from Test Dataset” indicates there are 97,682 positive sentences. “Actual Negative Sentiment Sentences from Test Dataset” points to 94,965 negative sentences. At the top of the matrix, “Predicted Sentiment Using RuSentiLex with Emoticons” shows the total number of sentences coded by the RUB Code. Each RuSentiLex sentiment has its own cell heading. The RUB Code categorised 72,927 as positive, 92,590 as negative, 5,459 as neutral, and 21,671 as ambiguous for both test datasets. The interior of the confusion matrix (identifiable by the thick, black border surrounding it) separates categorisation results for the two different test datasets. The boxes coloured light-grey indicate accurate classifications (the number of sentences given the correct sentiment). Because there are only positive sentiment and a negative sentiment test datasets, there are only two light-grey boxes. The uncoloured, white boxes tally the SA program’s errors: the false positives and false negatives.

Of the 72,927 predicted by the RUB Code to have positive sentiment, in fact 67,134 sentences were accurately predicted and 5,793 were false-positives. Of the 92,590 sentences predicted to be negative sentiment-bearing, 78,769 were correct predictions while 13,821 sentences were incorrectly coded (false-positives). Because none of the test datasets had neutral or ambiguous sentiment sentences, all these sentiment predictions are false-negatives. For the positive sentiment test dataset, the false-negatives include 13,821 negative sentiment, 3,487 neutral sentiment, and 13,240 ambiguous sentiment.

Unfortunately, there are no open source, Russian-language datasets to test neutral or ambiguous sentiment. Therefore, the RUB Code’s ability to predict sentiments has not been tested.

While this is a limitation, the RUB Code is still fit-for-purpose to track policymaker sentiment. The code can adequately discern between positive and negative sentiment (with F1 scores of 78 and 83 percent respectively). This handles the fundamental task of deciding whether policymakers are for or against an issue. Ambiguity and neutrality are, arguably, less important to when trying to discover policymaker positions.

A selection of results of the RUB Code’s sentiment analysis of the RUB Corpus can be viewed on the Data Visualistions page.

Contact

For any issues with the RUB Corpus and Code repositories, please use GitHub.

For general questions about this project or any ideas for academic collaboration, contact Peter Braga at: pjbraga.rubcc@gmail.com.

Page References

Dey, B. (2018, October 18). An Introduction to Sentence-Level Sentiment Analysis with sentimentr. Open Data Science Conference. Available at: https://opendatascience.com/an-introduction-to-sentence-level-sentiment-analysis-with-sentimentr/.

Friedl, J. E. F. (2006). Mastering regular expressions (3rd ed). O’Reilly. Available at: https://www.oreilly.com/library/view/mastering-regular-expressions/0596528124/.

Liu, B. (2015). Sentiment analysis: Mining opinions, sentiments, and emotions. Cambridge University Press.

Loukachevitch, N., & Levchik, A. (2017). Russian Sentiment Lexicon RuSentiLex [Open Source Repository]. Labinform.ru. Available at: http://www.labinform.ru/pub/rusentilex/index.htm.

Loukachevitch, N., & Levchik, A. (2016). Creating a General Russian Sentiment Lexicon. Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC’16), 1171–1176. Available at: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/volumes/L16-1/.

Mitchell, R. (2015). Web scraping with Python: Collecting data from the modern web. Available at: http://www.myilibrary.com?id=798887.

PyData Development Team. (2019, February 3). Pandas Documentation: Whats New in 0.24.1. Available at: https://pandas.pydata.org/pandas-docs/stable/whatsnew/v0.24.1.html.

Reitz, K. (2019, February 18). Requests-HTML (version 0.10.0). GitHub. Available at: https://github.com/psf/requests-html.

Richardson, L. (2019, January 7). Beautiful Soup 4.7.1 (HTML parser). Available at: https://www.crummy.com/software/BeautifulSoup/bs4/download/4.7/.

Rubtsova, Y. (2015). Constructing a corpus for sentiment classification training. Software & Systems, 27, 72–78. Available at: https://doi.org/10.15827/0236-235X.109.072-078.

Sarkar, D. (2019). Text Analytics with Python: A practical real-world approach to gaining actionable insights from your data. APRESS.

Schmidt, T., & Burghardt, M. (2018). An Evaluation of Lexicon-based Sentiment Analysis Techniques for the Plays of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. Proceedings of the Second Joint SIGHUM Workshop on Computational Linguistics for Cultural Heritage, Social Sciences, Humanities and Literature, 139–149. Available at: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/W18-4516.

Segalovich, I. (2003). A Fast Morphological Algorithm with Unknown Word Guessing Induced by a Dictionary for a Web Search Engine. MLMTA, 273–280. Available at: https://dblp.uni-trier.de/db/conf/mlmta/mlmta2003.html.

Seleznev, D. (2015). Yandex Speller: Documentation Page. Available at: http://yandex.ru/dev/speller/doc/dg/concepts/About-docpage/.

Sukhonin, D. (2018). pymystem3: Python wrapper for the Yandex MyStem 3.1 morpholocial analyzer of the Russian language. (0.2.0) [Python; OS Independent]. Available at: https://github.com/nlpub/pymystem3.

Van Rossum, G., & Drake, F. L. (2018, October 20). Python 3.7.1. Available at: https://www.python.org/downloads/release/python-371/.

Vīksna, R., & Jēkabsons, G. (2018). Sentiment Analysis in Latvian and Russian: A Survey. Applied Computer Systems, 23(1), 45–51. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2478/acss-2018-0006.